EPHRAIM PELEG

MY STORY

Ephraim Peleg was born Ferdynand Verderber in 1936 in Krakow, Poland. A survivor of the Holocaust, Peleg was sent to Israel when he was nine years old with his younger brother Zvi after learning that both parents were killed in the Nazi concentration camps. Before leaving Krakow, his father’s former colleagues at the art supply store which he managed before his imprisonment, gave young Ephraim a palette of paints to take with him on his journey to Israel. Ephraim brought the paint palette with him to Kibbutz Beit HaShita, his new home in Israel and vowed that he would not use the paints until he learned how to properly paint with them. Ephraim never forgot the palette of paints that he brought from Poland, one of the few physical connections that remained with his lost father, and eventually learned how to paint.

After finishing school and his army service, he studied at the Avni Institute of Art and privately with well-known artists such as Marcel Janko, Josef Zaritsky, Chaim Kive, and Ernst Fuchs. Later, while living in Jerusalem, he worked as an Assistant Instructor of Sculpture at the Bezalel Academy of Art, organized the after-school art program for the entire city, and taught art for UNESCO.

Peleg relocated to the United States in 1978 when he was commissioned to create a large scale sculpture for Cedar Crest College in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Since then, he has created outdoor sculptures for several sites in Pennsylvania—Lehigh University, Temple University, University of Pennsylvania, and B’nai Brith House. His most recent outdoor sculptures were installed in Veteran’s Memorial Park, Edgewater, NJ (overlooking the Hudson River) and Leonia NJ (Sculpture for Leonia). He has participated in major invitational outdoor exhibits in Chesterwood, Massachusetts and Philadelphia (Outdoor Sculpture’80 and Outdoor Sculpture “82. In 2002, Peleg represented Israel in Sculpture 2000 International in New London Connecticut.

I came to the United States when I was commissioned to create a large scale interactive sculpture for Cedar Crest College in Allentown, Pennsylvania in 1978. Since then, I was created outdoor sculptures for Lehigh University, Temple University, University of Pennsylvania, and B’nai B’rith House. Participated in major invitational outdoor exhibits such as Chesterwood (Massachusetts) and Cheltenham (Pennsylvania) and has exhibited broadly throughout Israel, Europe, and the United States in museums and galleries in one man and group shows.

Large and small scale sculptures for private and public collections are fabricated from metal, wood, stone, and other media. As a result of lost childhood and the loss of a son, Avihu in the War in Lebanon in 1982, I often relies on powerful forms and vibrant primary colors that appeal to children and the creative spirit in all of us; this is especially true of kinetic wall paintings that allow viewers to interact with the work by moving pieces and changing compositions.

SEXTET SERIES

SAILS

Veterans Memorial Park

Eedgwater, New Jersey

Overlooking the Hudson River and George Washington Bridge

I believed that survival relied on strength and clear goals and that survivors should not view themselves as victims, but rather the underpinnings for new life and renewal. I began constructing sculptures where I used repetition of more angular forms (often of six figures, each representing one million souls) to convey the strength and unity that has emerged from the murder of the six million

Ephraim Peleg

The Three Rings

Lehigh University

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

INTERACTIVE SERIES

INTERACTIVE SERIES

The Three Rings

Lehigh University

Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

The famous Ring sculpture… is a common sight to most Lehigh students, although very few students know the origin of the piece. A general viewer consensus is that the rings have some kind of symbolic meaning that no one understands, and that they’ve seen people moving them around. For a community that does not seem to understand the significance of some art objects, this response from the Lehigh people is precisely what the artist intended.

Ephraim Peleg

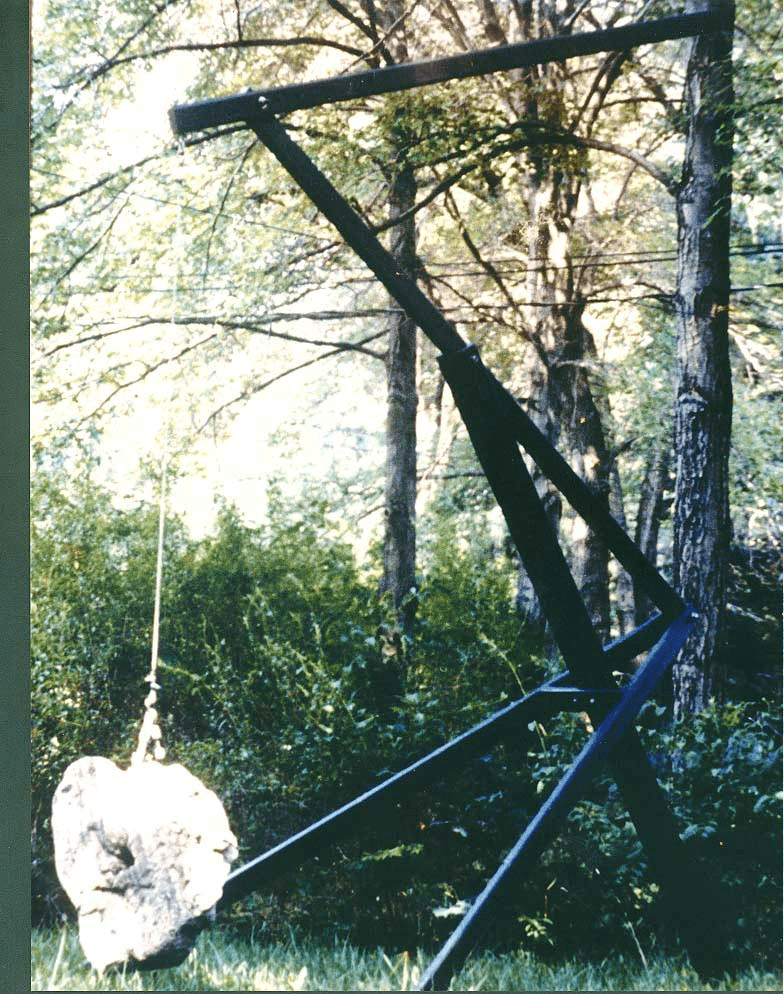

CABLEWORKS

David’s Stone Exhibited In Sculpture 2000 New London, Connecticut

“Peleg’s David’s Stone uses …rationalized geometry to suggest a more personalized symbolism. The stone’s mass is supported by a steel cable suspended flighty geometric hollow steel The weight of the stone is elegantly balanced, but we cannot escape the physical tension which seems destined to pull the sculpture apart and return its elements to the ground.”

Sculpture Magazine, November 2000,Volume 19, number 9 , p 62

IMAGINATION SERIES AND OTHERS

Sculpture for Leonia

Leonia, New Jersey

FLOWERS of steel

Many of my works area interactive and others incorporate playful themes to break down barriers between art and the public.

EPHRAIM PELEG

ARTIST STATEMENT

Originally trained as a painter, my fascination with sculpture began during my stay in London when the atmosphere and the light became colder and less vibrant for me. This was a drastic change from the warmth and brightness of Israel where I grew up. Unlike in my paintings, repetition became a recurrent theme in my three dimensional works.

My traumatic experiences during the Holocaust where both my parents were killed left me with a lost childhood, and these early experiences affected my approach to art. Perhaps the most influential event in more recent years to shape the evolution of my art was the death of my 19 year old son in Israel’s war with Lebanon (1982). This difficult loss caused me to refocus on my feelings about the Holocaust and to create sculpture that was more symbolic. I believed that survival relied on strength and clarity, and that survivors should not be viewed as victims but as the underpinning for new life and renewal. I began constructing pieces where I used repetition (usually six figures with each representing one million souls) and sharply defined forms to convey the strength and unity that has emerged from the death of the six million. Sometimes the six forms stand separately and sometimes they are attached so that they emerge as one unique creation. In some sculptures, each of the six forms is painted with a different bright color which seduces even very young viewers to become engaged with the work. These vibrant colors also symbolize hope and highlight the fact that each of the six million were unique individuals.

Repetition of a form continues to be an integral element of my work. Using different colors, shapes and materials, I try to communicate my sense of how omnipresent repetition is in all aspects of life. In order to make my work more accessible to the broad public–both young and old–I also often use interaction and playful themes as tools to break down barriers.

My belief in the importance of the survival of all people continues to be the inspiration for new works.